With Lasers and Daring, Doctors Race to Save a Young Man’s Brain

Written on Monday, December 25, 2006 by Gemini

OPERATING ROOM 14, Dec. 12, 9:30 a.m. — “I always prep my own patients,” Dr. David J. Langer said. “It relaxes me.”

He picked up a sponge soaked in antiseptic and began scrubbing the shaved skull of Chris Ratuszny, 26, a mechanic from Lindenhurst, N.Y.

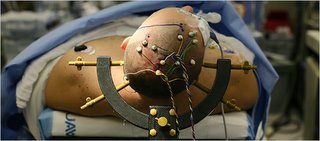

Mr. Ratuszny lay on the operating table, anesthetized and oblivious. His head jutted out past the end of the table, supported by four pins that had been screwed into his skull. The pins were attached, like spokes in a wheel, to a semicircular frame — surreal but standard, the hardware typically used to immobilize the head for brain surgery. A thick purple line had been drawn from his neck to the top of his head, to guide the scalpels.

He was about to become the first person in the United States to undergo an operation involving the use of an excimer laser to treat a giant brain aneurysm, a dangerous ballooning of an artery that could burst and kill him or leave him with devastating brain damage. The aneurysm was too big for the most common treatments, which involve clips or metal coils; it required bypass surgery on an artery in the brain.

The laser is not approved for brain surgery in the United States, but Dr. Langer got permission from the Food and Drug Administration to use it on an emergency basis for Mr. Ratuszny (ra-TOOSH-nee) last Tuesday at Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan. The Dutch neurosurgeon who devised the laser procedure, Dr. Cornelius Tulleken, flew in from the Netherlands to help. He has performed the operation on about 300 patients in Europe.

Dr. Tulleken’s technique involves a seemingly small variation on the standard procedure and takes just a few minutes in an eight-hour operation. But it could make all the difference for patients like Mr. Ratuszny, said Dr. Langer, who traveled to Utrecht in 1999 to learn the procedure from Dr. Tulleken. The advantage of the laser is that it lets surgeons operate without clamping a major artery in the brain — a step required in the standard operation, but one that can cause a stroke.

“It’s a high-risk operation in the best of hands,” Dr. Langer said.

He estimated that the laser could reduce the risk of stroke from bypass surgery for aneurysms to 12 percent, from 15 percent. But comparative studies have not been done. Some surgeons are skeptical, while others are eager to learn the technique, and it has begun to catch on in Europe, Dr. Tulleken said. A neurosurgeon from Chicago came to New York just to see how Mr. Ratuszny’s procedure was done.

The laser definitely makes the operation easier, Dr. Langer said, because just knowing that the brain arteries are still open takes enormous time pressure off the surgeon during critical parts of the operation. To him, that alone makes it worthwhile.

“If it was me, my head, and there was a new device that would allow me to have this operation without occluding an artery, that’s what I’d want,” Dr. Langer said.